This is part of our ongoing SpotOn Sports: The Data of Cricket series, where leading pundits tackle the toughest questions in cricket by using data & analytics.

Everyone feels that modern white ball cricket has become a batsman’s game. The first two weeks of the World Cup has definitely brought bowlers into it a little bit more. Personally, I have loved the fierce contest between bat and ball so far.

The World Cup so far

What I have enjoyed the most is the variety of the pitches. The two Trent Bridge pitches used so far are a great example. The Pakistan-West Indies match offered pace and bounce, while the Pakistan-England encounter was played on a flat pitch for which the Trent Bridge has become famous. Cardiff pitches have seen teams being bowled out for nearly under 200 in three out of four innings, while England ended up scoring 380 at the same ground. At the same time, 300 has been crossed at The Oval in three out of four innings.

The World Cup has not only been an exhibition for fast bouncers and swinging good length balls, but also some spin. Half the teams are from the subcontinent and depend heavily on their spin resources. The pitches have offered them a little bit of spin and grip, helping them bag half the wickets taken by their team. India’s leg-spinners ran through South Africa’s middle order, Bangladesh’s off-spinners cleaned up New Zealand’s top six, and Afghanistan’s spin trio bowled out Sri Lanka. As the tournament progresses, I’d like for some of the pitches to spin, so that batsmen are tested on that part of their game, too.

The delicate balance between bat and ball

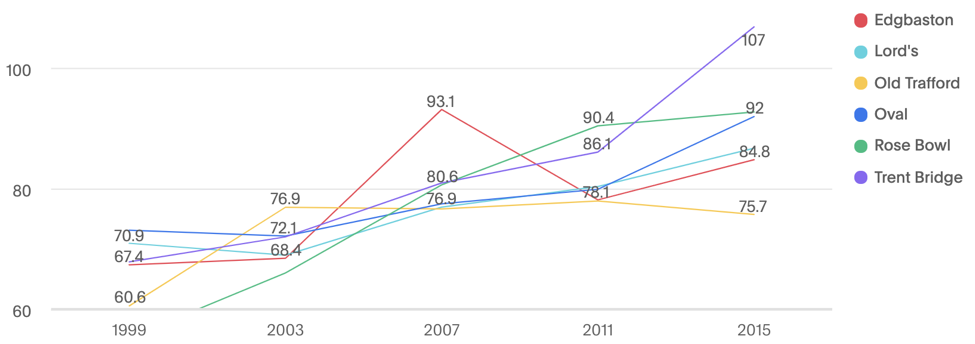

The balanced contest between bat and ball is a welcome change from the rate at which runs have been scored at the English venues in recent years. Since 2015, all the World Cup venues where 5 or more matches have been played have seen a strike rate of 85+ runs per 100 balls, with the exception of Old Trafford. This exception makes the upcoming India-Pakistan contest on this ground even more exciting.

Batting strike rate at venues of Cricket World Cup 2019 where 5+ matches will be played

350 is the new 300. 300 is the new 250.

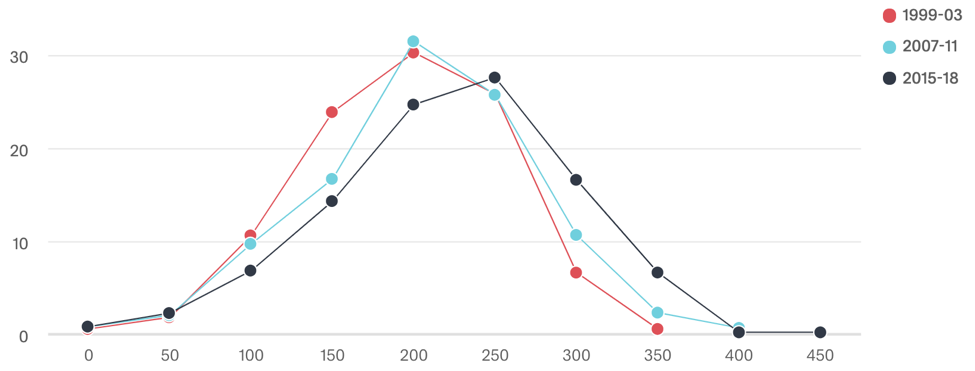

Red ball cricket is most exciting when conditions slightly favour bowlers, whereas white ball cricket is exhilarating when the balance tilts slightly towards batsmen. But in my opinion, the scales have tilted too far in ODIs. The distribution of ODI scores in the 21st century shows teams are scoring bigger, more frequently than before. From 1999, if we look at World-Cup periods in 4-year intervals, the curve shifts distinctly to the right for 2015-18.

Today, teams score 250+ more than half the time, compared to teams reaching this score one-third the time twenty years ago. The percentage of innings with a 300+ score has increased from 6% (1999-03) to 24% (2015-18). 400 has been breached 20 times since 2006 - 9 of these times have been since 2015.

Distribution of innings score for the super 8 teams (Aus, Eng, Ind, NZ, Pak, SA, SL, WI)

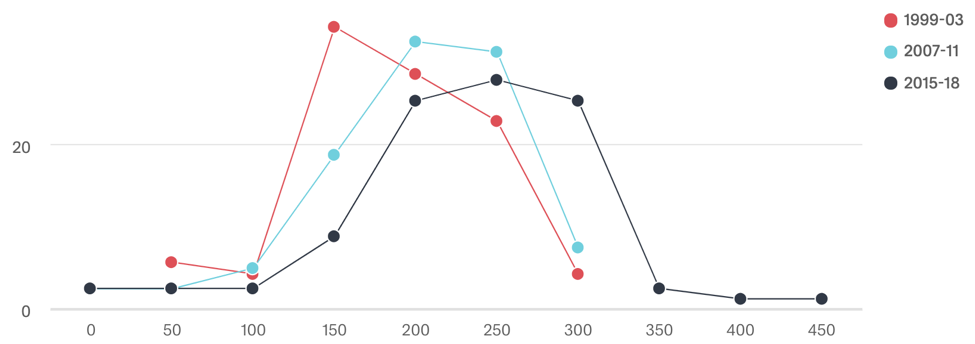

The shift in run scoring is even more pronounced for matches in England. The percentage of innings with a 300+ score has increased from 5% (in 1999-03; less than global) to 30% (in 2015-18; much more than global). How the game has changed since the last time England hosted the world cup!

Distribution of innings score for the super 8 teams when playing in England

Law changes in favour of batting

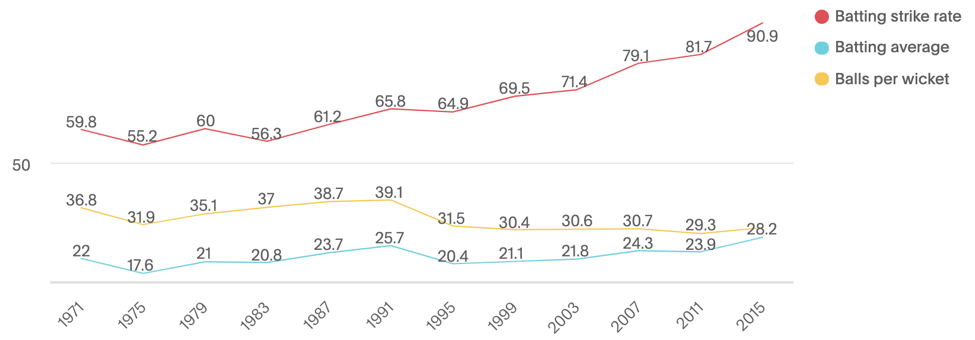

ODI cricket has indeed become a batsman’s game thanks to the law changes brought about by the ICC and their validation with the meteoric success of the T20 format. The less-swinging white ball and fielding restrictions in the first 15 overs tilted the balance slightly in favour of batting. T20 cricket brought about a revolution in batting style - and the spectators loved it. Rules were changed to suit power hitting. Powerplays with more fielding restrictions, flatter pitches and shorter boundaries help batsmen hit more 6s. Two new balls used from either end have taken reverse swing out of the game. Free hits and limits on bouncers have neutralized short pitched bowling.

England, the batting paradise

The T20 revolution hit the English shores later, but with more impact than the rest of the world. In 2015, we saw the home team led by Eoin Morgan adopt the most fearless batting approach the world had ever seen. It kicked in a virtuous cycle of English pitches being prepared flatter and boundaries shorter. In 2015-18, the batting strike rate in England has increased by 10%, while the bowling strike rate reduced by 5%. Batsmen playing in England make an astounding 10 more runs per 100 balls and average 4 more runs than anywhere else.

Evolution of run scoring in matches played in England

Restoring the balance

Pace bowlers have invented new variations like knuckle balls, wide yorkers, and slower balls. Spin bowlers have taken heavily to wrist spin to get more turn, making it harder for batsmen to read the variation from the hand.

In my opinion, however, more needs to be done to restore parity to the bowling trade and make the game more interesting. While the variety of pitches showcased at the World Cup have surely helped, my one proposition would be to have a serious look at the balls being used for white ball cricket. The white Kookaburra being used right now doesn’t seem to offer much, so trying other makes or going back to one new ball per innings could revive the art of reverse swing. White ball cricket is very watchable nowadays, but we must have one eye on future generations. We want young people watching to be inspired by bowlers just as much as batsmen.